It is time for my (kinda) regular reminder that marijuana is still illegal under federal (and state - under most circumstances) law!

In the United States it is illegal to possess marijuana. The possession of any amount is a criminal offense that carries a potential fine and/or imprisonment.

In Louisiana, it is illegal to possess marijuana (in any quantity); however, the possession of 14 grams or less is punishable by only a fine of up to $100. (NOTE: This is still. a. crime. It will still go on your rap sheet and you will still have to disclose it to potential employers.)

The one exception to the prohibition on possession under Louisiana law is that

Any person who is a patient of the state-sponsored medical marijuana program in Louisiana, and possesses medical marijuana in a form permissible under R.S. 40:1046 for a condition enumerated therein, a caregiver as defined in R.S. 15:1503, any person who is a domiciliary parent of a minor child who possesses medical marijuana on behalf of his minor child in a form permissible under 40:1046 for a condition enumerated therein pursuant to a legitimate medical marijuana prescription or recommendation issued by a licensed health professional authorized by R.S. 40:1046(B) to recommend medical marijuana to patients, or any visiting qualifying patient as defined in R.S. 40:1046.1 shall be exempt from the provisions of this Section. This Paragraph shall not prevent the arrest or prosecution of any person for diversion of marijuana or any of its derivatives or other conduct outside the scope of the state-sponsored medical marijuana program.

La. R.S. 40:966F(1).

With regard to traveling with marijuana, beyond its illegality under federal law, the chart below (thanks to statista.com for the chart!) shows the current state of legalization across the United States. Traveling to another state, even with a medical marijuana authorization from Louisiana, may still render you in legal trouble if it is not legal in the state to which you travel (or through which you travel).

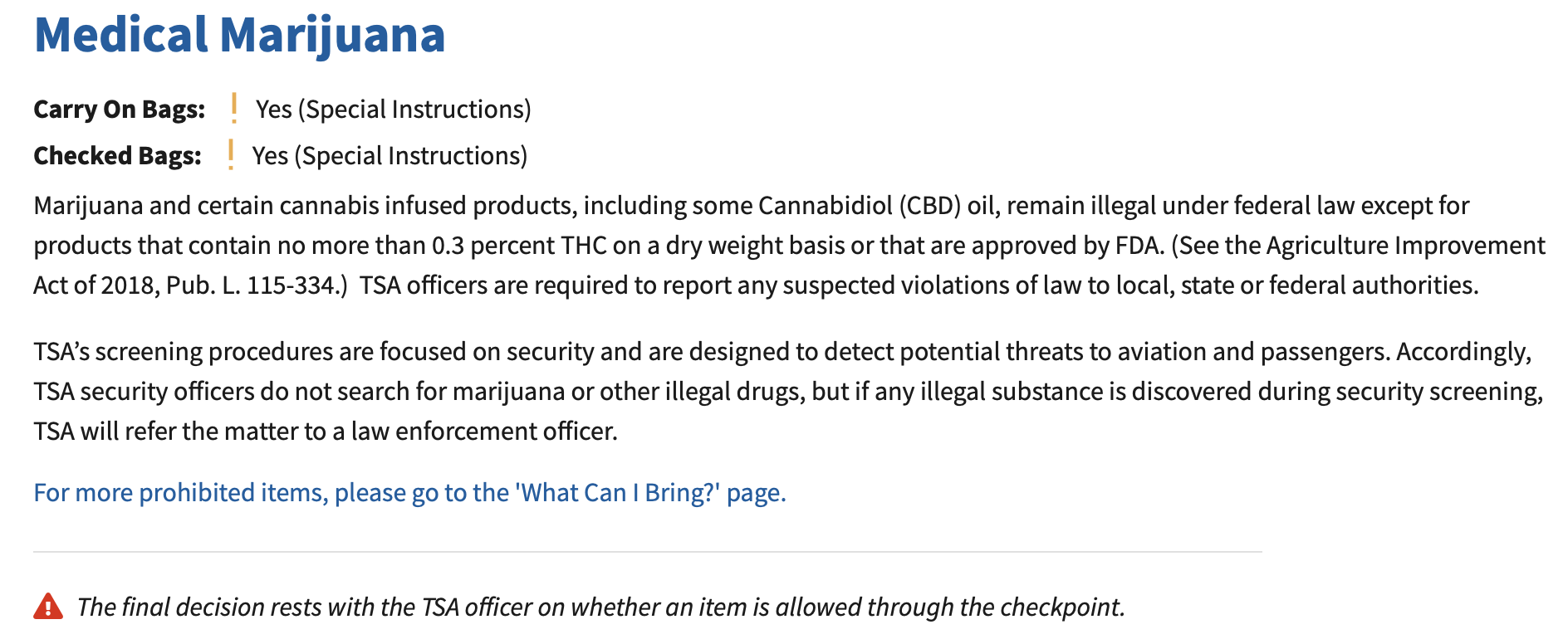

Finally, strangely, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) has an interesting perspective on air travel while carrying marijuana on their website:

The second paragraph of this blurb from the TSA’s website is, I think, the most important despite the permissiveness of the first paragraph.

If you or someone you know is being prosecuted for charges related to marijuana and would like to set up a consultation, give us a call at (318) 459-9111.